Montessori Philosophy

MONTESSORI DEVELOPED a new philosophy of education based upon her intuitive observations of children. This philosophy was in the tradition of Jean Jacques Rousseau, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and Friedrich Froebel, who had emphasized the innate potential of the child and his ability to develop in environmental conditions of freedom and love. Educational philosophies of the past, however, did not emphasize the existence of childhood as an entity in itself, essential to the wholeness of human life, nor did they discuss the unusual self-construction of the child Montessori had witnessed in her classrooms. Montessori believed that childhood is not merely a stage to be passed through on the way to adulthood, but is “the other pole of humanity”. She considered the adult to be dependent on the child, even as the child is dependent on the adult.

“We ought not to consider the child and the adult merely as successive phases in the individual’s life. We ought rather to look upon them as two different forms of human life, going on at the same time and exerting upon one another a reciprocal influence”.

Childhood as an Entity in Itself

The Child’s Inborn Powers

To explain the child’s self-construction, Montessori concluded he must possess within him, before birth, a pattern for his psychic unfolding. She referred to this inborn, psychic entity of the child as a “spiritual embryo.” This spiritual embryo is comparable to the original fertilized cell of the body. This cell does not contain the adult form in miniature but rather a predetermined plan for its

development. In a similar way, the child’s psychic growth is guided by a predetermined pattern, not visible at birth.

“The child is endowed with unknown powers, which can guide us to a radiant future. If what we really want is a new world, then education must take as its aim the development of these hidden possibilities.” – The Absorbent Mind, Maria Montessori

The Role of Environment and Freedom

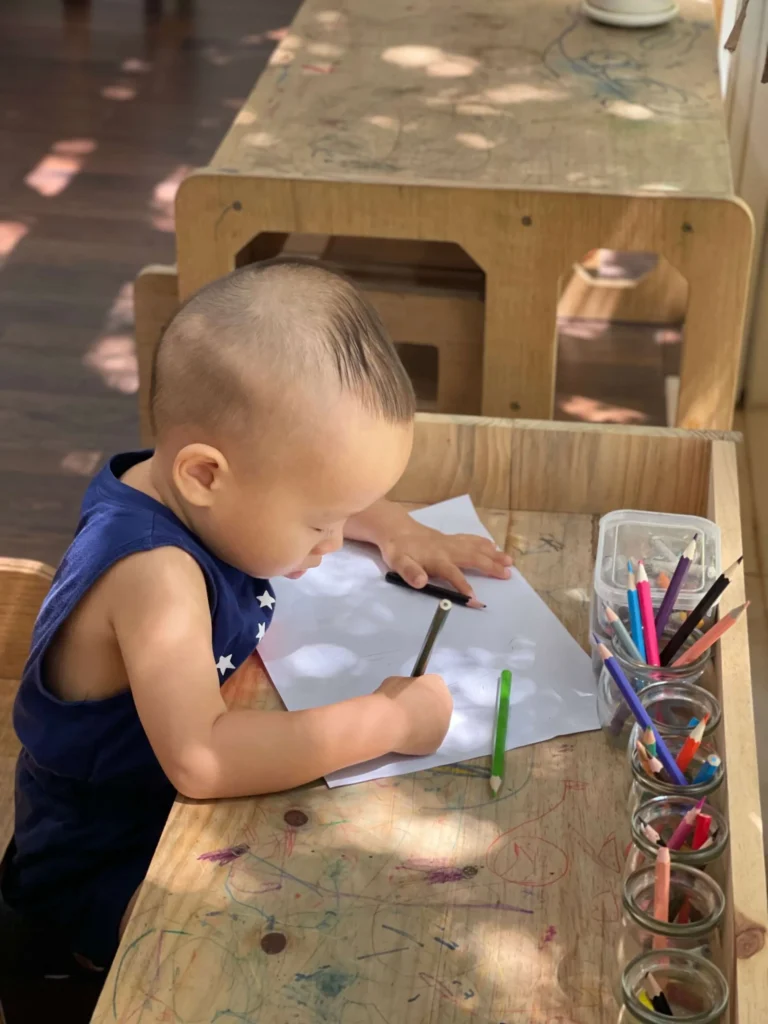

“The child gives us a beautiful lesson – that in order to form and maintain our intelligence, we must use our hands.” – Montessori

“At this age (between one and a half and two and a half years) children have a need to develop independence.” – Montessori

The Psychic Unity of Mind and Body

Montessori considered the dependent relationship of the child’s psychic growth to free interaction with his environment a natural result of his mental and physical unity. Western educational thought had been influenced by Descartes’ view of man as divided into two parts, the intellectual and the physical. Montessori now challenged this philosophical position and stated that the full development of psychic powers are not possible without physical activity.

“One of the greatest mistakes of our day is to think of movement by itself, as something apart from the higher functions.… Mental development must be connected with movement and be dependent on it. Educational theory and practice must become informed by this idea.”

If movement is curtailed, the child’s personality and sense of well-being is threatened. “Movement is a part of man’s very personality,

and nothing can take its place. The man who does not move is

injured in his very being and is an outcast from life.”

The Intrinsic Motivation of the Child

Montessori convinced that he possesses an intense motivation toward his own self-construction. The full development of himself is his unique, andultimate, goal in life. He spontaneously seeks to achieve this goal through an understanding of his environment. “He is born with the psychology of world conquest.” His emotional and physical health will literally depend upon this constant attempt to become himself.

Although the child has a predetermined psychic pattern to guide his striving for maturity, and a vital urge to achieve it, he does not inherit already established models of behavior which guarantee him success. Unlike other creatures of the earth, he must develop his own powers for reacting to life. He has, however, been given special “creative sensitivities” to help him accomplish this difficult task. These inner sensitivities enable him to choose from his complex environment what is suitable and necessary for his growth. The whole psychic life of the child rests upon the foundation these sensitivities make possible. A delay in their awakening will result in an imperfect relationship between the child and his environment. “Not feeling attraction, but revulsion, he fails to develop what is called ‘love for the environment’ from which he should gain his independence by a series of conquests over it.”

These transient faculties or aids exist only in childhood, and give no evidence of their existence in the same form and intensity much after the age of six. Montessori considered them proof that a child’s psychic development does not take place by chance, but by design. She identified two such internal aids to the child’s development: the Sensitive Periods and the Absorbent Mind.

There are three main elements of intrinsic motivation: being able to act independently, feeling that one’s efforts matter, and developing satisfaction from the experience of mastery

The Sensitive Periods

Sensitive Periods are blocks of time in a child’s life when he is

absorbed with one characteristic of his environment to the exclusion of all others. They appear in the individual as “an intense interest for repeating certain actions at length, for no obvious reason, until —because of this repetition—a fresh function suddenly appears with explosive force.” The special interior vitality and joy the child exhibits during these periods result from his intense desire to make contact with his world. It is a love of his environment that compels him to this contact. This love is not an emotional reaction, but an intellectual and spiritual desire.

If the child is prevented from following the interest of any given Sensitive Period, the opportunity for a natural conquest is lost

forever. He loses his special sensitivity and desire in this area, with a disturbing effect on his psychic development and maturity.

Therefore, the opportunity for development in his Sensitive Periods must not be left to chance. As soon as one appears, the child must be assisted. The adult has not to help the baby to form itself, for this is nature’s task, but he must show a delicate respect for its manifestations, providing it with what it needs for its making and cannot procure for itself. In short, the adult must continue to provide a suitable environment for the psychic embryo, just as nature, in the guise of the mother, provided a suitable environment for the physical embryo.

1. Order

Order is the first Sensitive Period to appear. It is manifested early in the first year of life, even in the first months, and continues

through the second year. It is important to understand that Montessori saw a clear distinction between the child’s love of order

and consistency, and the mature adult’s milder pleasure and satisfaction in having everything in place. The child’s love of order is based on a vital need for a precise and determined environment.

Only in such an environment can the child categorize his perceptions, and thus form an inner conceptual framework with

which to understand and deal with his world. It is not objects in place that he is identifying through his special sensitivity to order, but the relationship between objects.

“He has an inner sense which is a sense not of distinction between things, so that it perceives an environment as a whole with interdependent parts. Only in such an environment, known as a whole, is it possible for the child to orient himself and to act with purpose; without it he would

have no basis on which to build his perception of the relationship.”

The child manifests his need for order to us in three ways: he shows a positive joy in seeing things in their accustomed place; he often has tantrums when they are not; and, when he can do so himself, he will insist on putting things back in their place

2. Tongue and hands

A second Sensitive Period appears as a desire to explore the environment with tongue and hands. Through taste and touch, the child absorbs the qualities of the objects in his environment and eeks to act upon them. Equally important, it is through this sensory and motor activity that the neurological structures are developed for language.

The child must be exposed to language during this Sensitive Period, or it will not develop, as the account of the “wild boy” of Aveyron.

The child in our culture is usually surrounded by the sounds he needs in establishing language. The use of his hands during this Sensitive Period is often another matter, although it is equally

essential to his development. He must have objects to explore in order to develop his neurological structures for perceiving and

thinking, just as he must be exposed to the world of human sound in order to develop his neurological structures for language. During this period the child is usually surrounded by adult objects. It is also important to remember that the child’s actions are not due to random choice, but directed by his inner needs for development. “Now the child’s movements are not due to chance. He is building up the necessary co-ordinations for organized movements directed by his ego, which commands from within.” Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that the adult be guided by tolerance and wisdom when placing any necessary limits on the child’s need to touch and taste during this period.

3. Walking

The Sensitive Period for walking is probably the most readily identified by the adult. Montessori viewed this time as a second birth for the child, for it heralded his passing from a helpless to an active being.

One fact Montessori observed during this period is not always recognized by adults: children at this time love to go on very long walks. Montessori found that children as young as a year and a half can walk several miles without tiring. The child does not walk, however, as an adult, who walks steadily with an external goal in mind.

The small child walks to develop his powers, he is building up his being. He goes slowly. He has neither rhythmic step nor goal. But things around him allure him and urge him forward. If the adult would be of help, he must renounce his own rhythm and his own aim.

“It is underestimated how long a child can walk for, once they are allowed to do it at their pace, however the adult must be aware that they have no concept of time and they love to explore.”

As soon as the child has acquired this form of independence [walking] he begins to carry heavy things and to do difficult things. We call it maximum effort. He climbs on chairs, he goes upstairs, he does all kinds of things which require a great effort.

“It is of the utmost importance that the adult be guided by tolerance and wisdom when placing any necessary limits.” – Montessori

4. Small objects

A fourth Sensitive Period involves an intense interest in objects so

tiny and so detailed they may escape our notice entirely. The child may become absorbed by tiny insects barely visible to the human eye. It is as if nature set aside a special period for exploring andappreciating her mysteries, which will later be overlooked by a busy adult.

“It is this sensibility [sensitive periods] which enables a child to come into contact with the external world in a particularly intense manner.

Every effort marks an increase in power.“

5. The social aspects of life

A fifth Sensitive Period is revealed through an interest in the social aspects of life. The child becomes deeply involved in understanding the civil rights of others and establishing a community with them. He attempts to learn manners and to serve

others as well as himself. This social interest is exhibited first as an observing activity, and later develops into a desire for more active contact with others.

Montessori considered her discovery of the Sensitive Periods as one of her most valuable contributions and their further study an important task for educators.

Before these revelations of true child nature, the laws governing the building up of psychological life had remained absolutely unknown. The study of the Sensitive Periods as directing the formation of man may become one of the sciences of the greatest practical use to mankind.

The Absorbent Mind

The Sensitive Periods describe the pattern the child follows in gaining knowledge of his environment. The phenomenon of the

Absorbent Mind explains the special quality and process by which he accomplishes this knowledge.

Because the child’s mind is not yet formed, he must learn in a different way from the adult. The adult has a knowledge of his

environment on which to build, but the child must begin with nothing. It is the Absorbent Mind that accomplishes this seemingly impossible task. It permits an unconscious absorption of the environment by means of a special pre-conscious state of mind. Through this process, the child incorporates knowledge directly into his psychic life. “Impressions do not merely enter his mind, they form it, they incarnate themselves in him.” An unconscious activity thus prepares the mind. It is “succeeded by a conscious process which slowly awakens and takes from the unconscious what it can offer.” The child constructs his mind in this way until, little by little, he has established memory, the power to understand, and the ability to reason.

This creating by absorption extends to all the mental and moral characteristics that are regarded as fixed in humanity or race or community and include patriotism, religion, social habits, technical dispositions, prejudices, and, in fact, all items that make up the sum-total of human personalty.

By the age of three, the unconscious preparation necessary for later development and activity is established. The child now embarks on a new mission, the development of his mental functions. “Before three, the functions are being created; after three, they develop.”

“Children have an absorbent mind. They absorb knowledge from the environment without fatigue. […] This is the moment in the life of man when we can do something for the betterment of humanity and further brotherhood.” – Montessori

A New Goal for Education

Montessori philosophy states, then, that the child contains a “spiritual embryo” or pattern of psychic development even before

birth. The two conditions of an integral relationship with the environment and freedom for the child must exist if this embryo is to develop according to its plan. The goal of the child is to so develop, and he is intrinsically motivated toward this goal with an intensity unequalled in all of creation. Since he must create himself

out of undeveloped psychic structures, he has been given special internal aids for the task: the Sensitive Periods and the Absorbent Mind.

Adults must provide children with an open environment that allows them to freely go through all stages of development, known as Sensitive Periods, in order to perfect themselves. This is the ultimate goal of Montessori education.

The Natural Laws of Development

One of the most important of those Montessori observed is the law of work: the children have achieved an integration of self through their work. They appeared immensely pleased, peaceful, and rested after the most strenuous concentration on tasks they had freely chosen to do.

Among the revelations the child has brought us, there is one of fundamental importance, the phenomenon of normalization through work.… It is certain that the child’s aptitude for work represents a vital instinct; for without work his personality cannot organize itself and deviates from the normal lines of its construction. Man builds himself through working. It is because work helps the child to become truly himself that he is driven to his constant activity and effort.

1. Law of maximum effort

The child cannot stand still; he is impelled to a continuous conquest. “To succeed by himself he intensifies his efforts.” Because it fulfils his individual destiny, he appears rested and satisfied after his labours, despite their intensity.

It is obvious that the work of the child is very unlike the work of the adult. Children use the environment to improve themselves; adults use themselves to improve the environment. Children work

for the sake of the process; adults work to achieve an end result. “It is the adult’s task to build an environment superimposed on nature, an outward work calling for activity and intelligent effort; it is what we call productive work, and is by its nature social, collective and organized.” He must, therefore, follow a law of exerting minimum effort to attain maximum productivity. He will look both for gain and for assistance. The child seeks no assistance in his work. He must accomplish it by himself.

Because of the social nature of his life, which is neither adaptive nor productive to adult society, the contemporary child is largely removed from it. He is exiled in a school where too often his capacity for constructive growth and self-realization is repressed. This problem in contemporary civilization increases as the adult’s

role becomes ever more complex. In primitive societies, where work was simple and could be carried out at a relaxed pace, the adult could coexist with children in his working environment with less friction. The complexity of modern life is making it increasingly difficult for the adult to suspend his own activities “to follow the

child, adapting himself to the child’s rhythm and the psychological needs of his growth.”

2. Law of independence

A second principle revealed through the child’s development is the law of independence. “Except when he has regressive tendencies, the child’s nature is to aim directly and energetically at functional independence. Development takes the form of a drive toward an ever greater independence.”

He uses this independence to listen to his own inner guide for actions that can be useful to him. “Inner forces affect his choice, and if someone usurps the function of this guide, the child is prevented from developing either his will or his concentration.” It is because the adult persists in just this usurping that much of the child’s potential is never realized.

Full personality development is totally dependent on progressive release from external direction and reliance.

3. Power of attention

A third psychic principle involves the power of attention. At a certain stage in his development, the child begins to direct his

attention to particular objects in his environment with an intensity and interest not seen before. “The essential thing is for the task to arouse such an interest that it engages the child’s whole personality.” This is not the point of arrival, but the point of

departure, for the child uses this new ability for concentration to consolidate and develop his personality. At first, he will be attracted to materials that appeal to his instinctive interest, such as bright colors. As he has more experience, however, he builds up an internal knowledge of the “known,” which now excites expectation and interest in the novel unknown.

The child concentrates on those things that he already has in his mind, that he has absorbed in the previous period, for whatever has been conquered has a tendency to remain in the mind, to be pondered.

In this way, a discerning interest based on intellect replaces an instinctive interest based on primitive impulses. When the child achieves this focusing of attention based on intellectual interest, he grows calmer and more controlled. His pleasure in his acts of concentration is obvious, and he appears rested and fulfilled. Montessori saw these outward manifestations of pleasure as evidence of the constant element of internal formation taking place in the child.

4. Law of the will

After internal coordination is established through the child’s ability for prolonged attention and concentration, a fourth psychic principle involving the will is revealed. The will’s “development is a

slow process that evolves through a continuous activity in relationship with the environment.” The child chooses a task and

must then inhibit his impulses toward extraneous movements. An inner formation of the will is gradually developed through this adaptation to the limits of a chosen task. Decision and action then are the bases for the will’s development. Lectures on what the child ought to do are of no use, since they do not involve decision or action. Similarly, it is not moral vision, but this inner formation developed by exercising the will, that gives the strength to control

one’s actions. Because traditional schooling severely limits the

child’s opportunities for choice and action, Montessori felt it “not

only denies the child every opportunity for using his will but directly obstructs and inhibits its expression.”

Montessori observed three stages in the development of the child’s will.

First, The repetition of an activity

This repetition occurs after his attention has been polarized and he has achieved a degree of concentration in one of the exercises. The child may repeat the exercise’s cycle of activity many times with obvious satisfaction. If adults persist in interrupting the child during this cycle of repetition, his self-confidence and ability to persevere in a task are severely jeopardized. Constant interruption during this time is so upsetting to the child that Montessori felt it caused him to live in a state “similar to a permanent nightmare.”

This “achievement, however trivial to the adult, gives a sense of power and independence to the child.” – Montessori

Second, Self-discipline as a way of life

After achieving independence and power over his own movements, the child moves to a second stage in the development of the will, where he begins spontaneously to choose self-discipline as a way of life.He makes this choice for his own liberation as a person. It is a point of departure, not an end, which leads him to self-knowledge and self-possession. It is a state characterized by activity, not the immobility that is often referred to as “discipline” in the traditional school. In this stage the child makes creative use of his abilities, accepts the responsibility of his own actions, and complies with the limits of reality.

Third, The power to obey

After achieving self-discipline, the child reaches a third stage of the developed will involving the power to obey. This power is a natural phenomenon, and “shows itself spontaneously and unexpectedly at the end of a long process of maturation.”

Montessori considered obedience and will as integral parts of the same phenomenon, obedience occurring as a final stage in the development of the will. In the little child’s life, as soon as he makes an action deliberately, of his own accord, this force has begun to enter into his consciousness.

When the final stage of this development is reached, obedience to the forces of life appears, and it is this obedience that makes possible the continuance of human life and society.

5. The development of the intelligence

A fifth psychic principle governs the key to understanding life itself. This is the “key which sets in motion the mechanisms essential to education.” Intelligence is defined as “the sum of those reflex and associative or reproductive activities which enable the mind to construct itself, putting it into relation with the environment.”

The beginning of intellectual development is the consciousness of difference or distinction in the environment. The child makes these perceptions through his senses; he must then organize them into an orderly arrangement in his mind. It will do him no good to have had contact with a stimulating and varied environment if it only results in a chaos of mental impressions. “To help the development of the intelligence is to help to put the images of the consciousness in order.” The first sign that this internal process is taking place will be quickness of response to stimuli, and the second will be the orderliness of these responses.

6. The child’s imagination and creativity

A sixth natural law governs the development of the child’s

imagination and creativity. These are inborn powers in the child that develop as his mental capacities are established through his interaction with the environment. The environment must itself be beautiful, harmonious, and based on reality in order for the child to organize his perceptions of it. When he has developed realistic and ordered perceptions of the life about him, the child is capable of the selecting and emphasizing processes necessary for creative endeavors. He abstracts the dominant characteristics of things, and thus succeeds in associating their images, and keeping them in the foreground of consciousness.” Montessori emphasized that this selective capability requires three qualities: a remarkable power of attention and concentration which appear almost as a form of meditation; a considerable autonomy and independence of judgment; and an expectant faith that remains open to truth and reality.

In addition to an environment of beauty, order, and reality, Montessori realized that the child needs freedom if he is to develop creativity—freedom to select what attracts him in his environment, to relate to it without interruption and for as long as he likes, to discover solutions and ideas and select his answer on his own, and to communicate and share his discoveries with others at will.

The child in the Montessori classroom is also free from the judgment by an outside authority that so annihilates the creative

impulse. This is in direct contrast to the traditional school setting, where the basis for evaluation is always outside the child.

7. The development of the emotional and spiritual life

Montessori believed the child possesses within him at birth the senses that respond to his emotional and spiritual environment and thereby develop his capacity for loving and understanding responses to others and to God. These inborn senses correspond to those possessed at birth for responding to the physical world and thereby developing the intelligence. The child achieves the development of the latter through the stimuli of the material world, but for the former he needs the stimuli of human beings. He is first aroused through a loving experience with his mother. Her love for him awakens his internal senses and makes possible, in turn, his loving responses to her. Once the child’s emotional awakening has thus occurred, he will begin to respond to the offer of loving relationships from others. It is the wealth of emotional material in others that will attract him, even as the richness of physical stimuli attract him to his material environment. Therefore, the free choice of the child must again be respected. If the adult has been careful to present the child with the means he needs for his development and to be always ready to help, but never to dominate, then the child will assuredly respond to the adult’s love and respect. Finally, he will begin responding to other children as well, showing an awareness and interest in their work and progress as well as his own.

To achieve emotional and spiritual maturity, the child must develop not only his internal capacity for love, but also his moral sense. Again, Montessori believed this to be an internal sense present at birth. For the development of the moral sense to take place, the child needs an environment in which good and evil are clearly differentiated.

8. Five periods of growth

Montessori outlined five such periods of growth by chronological age. The period from birth to three years is characterized by unconscious growth and absorption. The internal structure of emotional and intellectual development is being created by means of the Sensitive Periods and Absorbent Mind. This is a period of unequalled energy and intense effort for the child, for indeed his whole life will depend upon what he can accomplish. During the period between three and six, the child gradually brings the knowledge of his unconscious to a conscious level. By six, his inner formation of discipline and obedience has been established, and he has developed an internal model of reality on which to base his imaginative and creative efforts. Between six and nine, then, he is capable of building the academic and artistic skills essential for a life of fulfilment in his culture. In the period from nine to twelve, the child is ready to open himself to knowledge of the universe itself. It is similar to the earlier period from birth to three, when he eagerly absorbed everything in his environment.

However, he is now learning with his conscious mind, and, instead of being limited to his immediate environment, he can range as far as the cosmos itself. His intellectual interest for a lifetime will

depend upon his opportunities during this period. This is why his schooling at this time must include as complete an exposure to the

world as possible, and not be broken down into isolated units of subject matter as is now customary in traditional schools. The period from twelve to eighteen is the time for exploring more concentrated areas of interest in depth. The child should be choosing the pattern of endeavor he will follow for life, and so it is a period of limiting choices. This period of decision is postponed in our culture until a later age. Since it is usually not encouraged or even permitted at the natural age, unnecessary emotional and intellectual problems occur. The adolescent rebellion so taken for

granted in our culture is a phenomenon not seen in many other civilizations.

“This was the first time that we had evidence that the intelligence of man does not progress forward, becoming ever greater. At the different ages there are different mentalities. There is a form of mind in younger children that is different from that of older children.” – Montessori